Idomeni, a landscape that’s idyllic but not particularly humane. (The white dot on this picture’s right side, halfway between top and bottom, is the refugee camp.)

“Information” is as information does.

Idomeni, a landscape that’s idyllic but not particularly humane. (The white dot on this picture’s right side, halfway between top and bottom, is the refugee camp.)

“Information” is as information does.

A short ways before the Macedonian border, I decide to stop for gas. To me, no matter what, a border means embarking on yet another journey into the unknown. And I’m fond of being well organized when I do so. Here, the E75 epitomizes my idea of the classic Balkan highway: straight as an arrow as far as the eye can see, with two lanes, wide shoulders, and a double solid line in the center—whatever the exact meaning of that might be.

The gas station’s easy to make out from afar, but you can hardly see it at all once you’re up close. The whole area is completely covered by refugee tents. So I plough my way through this little tent-village, and between 1,500 and 2,000 people (about half the population of the place I come from) keep me company while I fill up.

I decide to stick around a bit. And in the evening, I go out with some volunteer helpers. Suddenly, one of them puts a set of keys on the table.

It’s the house keys of a Syrian who gave it to him with the words: “Here, they’re for you—I don’t need them anymore.”

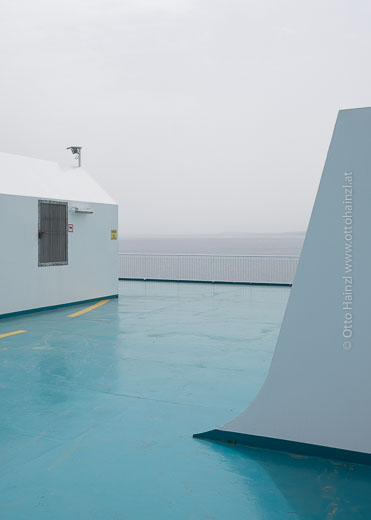

It’s time to say goodbye to the sea—to this sea, anyway. I’m looking forward to the next one.

Athens from the E75

Early arrival. I go off in search of the cleared-out refugee camp—“along the wall at the port,” as I’ve read. There are still tents here, of course. It hasn’t been cleared out, even if the press reported that it was. Seven in the morning. All’s quiet. But I do see a few people. A large port facility parking lot with painted markings on the ground and concrete barriers. These attempt to determine a structure. I walk around. The tents. About 100, I think. Beside them an asphalted area with two goal cages made of wood and orange netting. Well done. Football. Quiet still prevails.

A couple of campers are parked here. For the assistance efforts. There’s a paper sign that reads “Doctor” taped to one of them. Things generally seem organized, but the available resources are modest. Alongside the large building there are portable toilets, around 20 of them. And now I see the building’s entrance. It opens onto a whole warehouse full of tents, chock-full of tents. A couple of voices can be heard—but they can’t overcome the morning’s quiet. There’s a strong smell in the air. A bulletin board is covered with sheets of information on how to continue. Where to go—or not to go. In Arabic, in Farsi, and in English. The sun’s coming up. From now on, the outdoor tents will be at the mercy of the day’s heat.

Then I speak with a refugee and ask him how long he’s been at this camp. Two months—too long. He wants to continue on to Italy, where his family is. He knows the route. But he’s still sitting around here. I talk with a volunteer helper, a young man from Romania. “We help with food, chai and love. That’s what we can do.” He gets back to work.

This is one of two refugee camps here in Piraeus. It houses around 1,000 refugees, while the other holds more than 5,000. It provides help, but it wasn’t set up by the state.

.

I got the idea for this project several years ago. When I realized just how extensive the Europastrasse network is, even running into such roads in Asia, and when it became clear to me just how unclear to me and many others the underlying idea is, I decided to drive one of them from A to Z. But, “The map is not the territory.” What I’m learning about here is our continent, us.

Vardø has caught my interest. A village at the end of the world. Or that’s how it looks from my perspective, at least. (I admit that I often view the earth as being a flat disc.) And it’s to just this end that a certain Europastrasse leads. Why? At this road’s other end is Sitia, on Crete. Which is probably a bit better known, but I’m no more familiar with it. If it’s not at the end of the world, it’s at least at the end of Europe.

So the E75 becomes my Europastrasse of choice. I really like how, in running from north to south, from south to north, it traverses the entire continent and so many cultures that touch our own. Sitia, one of Europe’s southernmost points. Farther south than the Straits of Gibraltar, farther south than Sicily. Vardø, on the other hand, is a good ways north of the Arctic Circle, Continue reading